Addressing climate change through planned city extensions

The battle to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the unavoidable impacts of climate change – within the broader effort to achieve more sustainable development – may well be won or lost in cities. An important strategy that growing cities can embrace is the planned city extension, where great environmental benefits can be incorporated into the initial development process.

Cities emit a significant proportion of the world’s anthropogenic greenhouse gases. At the same time, urban areas are highly vulnerable to climate change. Tens of millions of urban dwellers around the world increasingly are being affected by rising sea levels and storm surges, heat stress, changing precipitation patterns, inland and coastal flooding, landslides, drought, increased aridity, water scarcity and air pollution. The effects of Hurricane Sandy in New York and New Jersey in 2013, as well as the more recent Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, have shown the potentially devastating effects of typhoons and storm surge on local populations and their livelihoods.

When urbanists take up the challenge of addressing climate change and achieving more sustainable development in cities, they may begin by dividing the urban space into two distinct geographic areas: the existing city and the expanding city. Each of these two geographic areas features its own set of challenges and suite of possible approaches. Infill development or brownfields redevelopment, for example, represent strategies for achieving more sustainable development patterns in existing urban areas. Improving conditions in existing cities is of paramount importance in regions such as Europe where population growth is stagnant. The present article, however, explores a critical strategy that growing cities can embrace as they expand into peri-urban lands and the non-urbanised periphery: planned city extensions.

Focusing on planned city extensions

Using planned city extensions as a strategy for addressing climate change is important, firstly because of long-term trends in population growth and location decisions. Even as the world population continues to grow, ever higher proportions of those people are choosing to live in urban rather than rural areas. While over half of mankind lives in urban areas today, it is estimated that by 2050 over two-thirds of all people will be living in such areas.

Authors of the recently published Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC estimate that, between 2000 and 2030, the urban footprint will increase between 56 and 310 per cent

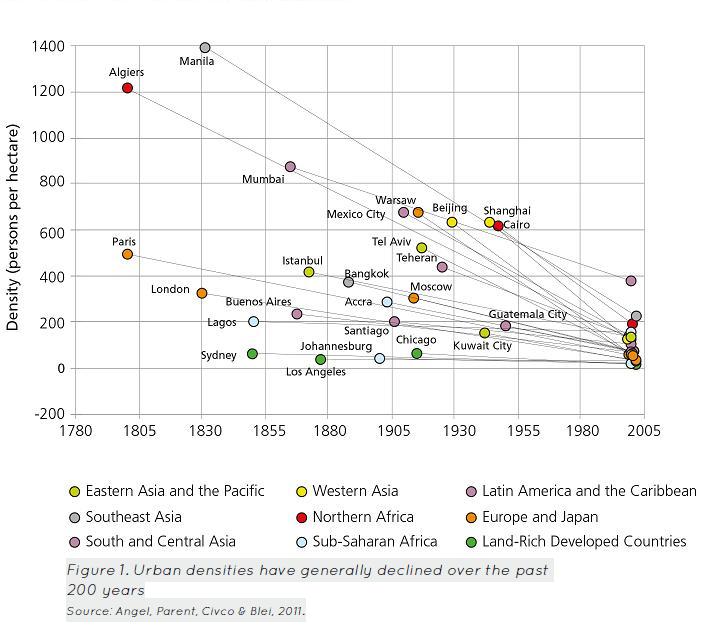

What kind of spaces will the urban dwellers of 2030, 2040 and 2050 occupy? Almost certainly a substantial proportion of these people – particularly in developing countries and emerging economies – will be living in newly urbanised areas. It will be impossible to accommodate all of them within the confines of existing urban boundaries. Cities are generally becoming less dense – a long-term trend (see Figure 1). Even if we manage to arrest or even reverse this trend through concerted densification efforts, developers will still need to convert a significant amount of land from rural to urban uses to accommodate burgeoning urban populations. In fact the authors of the recently published Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimate that, between 2000 and 2030, the urban footprint will increase between 56 and 310 per cent. They reckon that “55 per cent of the total urban land in 2030 is expected to be built in the first three decades of the 21st century”. Given that some significant amount of rural-to-urban land conversion will occur in coming decades, it behoves us to develop that land in as sustainable a manner as possible.

Given these circumstances, how can a planned approach to city extensions provide for more climate-friendly urban development? By designing urban areas well from the very beginning we begin to accrue substantial climate benefits and co-benefits now – and avoid locking in unsustainable development patterns that may require costly retrofits and redevelopment schemes in the future.

On the mitigation side, well-planned city extensions can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by providing for more compact urban development , with well-integrated public transport options and a mix of land use types. Today, such conditions are found more often in urban centres than in low-density, single-use-zoned suburbs. The problem is that this latter pattern of suburban development, which has prevailed in North America and elsewhere since World War II, results in higher emissions of greenhouse gases. For example, for the United States Glaeser estimated in 2009 what the ‘average household’ would emit if it settled in a high density central city and what it would generate in the suburbs. Of his review of 48 metropolitan areas he concluded that, in almost all cases, “carbon emissions are significantly lower for people who live in central cities than for people who live in suburbs.”

By designing urban areas well from the very beginning we begin to accrue substantial climate benefits and co-benefits now

Why does more compact urban development, be it in centre cities or city extensions, typically result in lower emissions? One reason is that shorter travel distances, and the greater viability and attractiveness of public transport, result in lower transport-related emissions. For New York City, for example, Glaeser estimated that an average resident “emits 4,462 pounds less of transport-related carbon dioxide [per year] than an average New York suburbanite.” Similarly the provision of other urban basic services such as district heating or solid waste collection is generally more efficient in more compact communities. This translates into lower energy costs, with correspondingly lower carbon emissions.

Well-planned city extensions can also confer adaptation and resilience benefits. Planners can, for example, map floodplains, and then require new development in those areas either to be flood-proofed or else prohibited entirely. Such measures reduce vulnerability to flooding (which in many locations is projected to increase under future climatic conditions). Planners of city extensions can also take steps to preserve functional ecological systems, e.g. watersheds that promote drainage and the absorption of storm water runoff. Preserving functionality makes ecosystem-based approaches to adaptation more viable options. In almost all cases such planning measures are more cost-effective when undertaken proactively, at the moment of urbanisation, rather than through costly and politically difficult reactive steps such as relocating families located in flood-prone areas, or trying to restore degraded ecosystems.

Other non-climate-related benefits

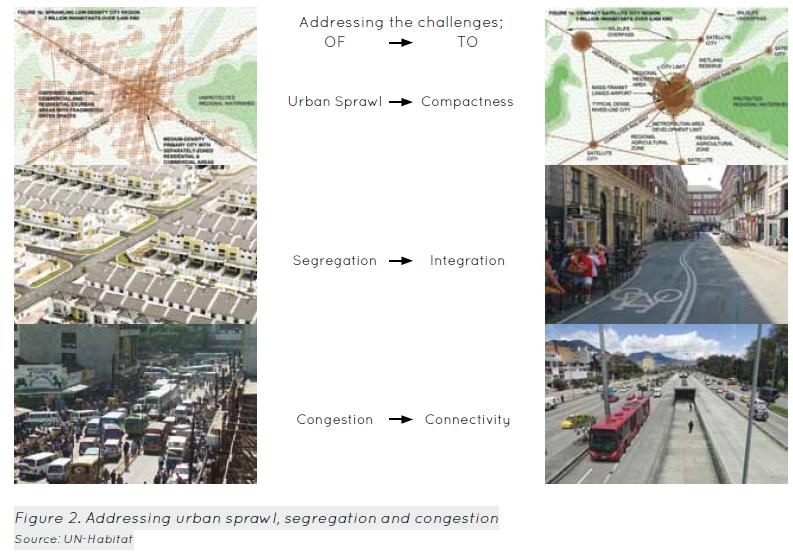

UN-Habitat typically looks at the urban development process through a broader lens of sustainability that takes into consideration climate ramifications. Both through planned city extensions and other approaches we promote the development of compact, integrated and connected cities (see Figure 2). This new urban paradigm confers a series of economic, social and environmental benefits.

Compact urban form helps to reduce land demand per capita. In addition to the considerable climate benefits discussed above, compact development also yields other benefits. For example, according to the New Climate Economy Report, a more compact and connected urban development built around mass public transport could “reduce urban infrastructure capital requirements by more than US$3 trillion over the next 15 years” (Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, 2014). In addition to such cost savings and improved access to basic services, analysts have also posited the economic development benefits of compact development, e.g. from improved agglomeration economics. The co-benefits of urban density have been covered extensively in academic literature and UN-Habitat publications, such as the Urban Patterns for a Green Economy series, e.g. on ‘Leveraging Density’ (UN-Habitat 2012).

Integration can be achieved by planning compatible activities and land uses in appropriate locations. This helps cities provide proximity to public services and jobs and hence reduce transport needs. Creating enough serviced and affordable land is essential for successful social integration and inclusive development, as well as for the provision of economic opportunity.

Connectivity. Sound urban design is important for providing connectivity within and between neighbourhoods. The street pattern should allow for densification and for future extension. Providing good public transport, as well as adequate infrastructure for walking and cycling, is important to avoid costly congestion, to reduce emissions and pollution, and to facilitate access to jobs and services.

Case Study: Villa El Salvador

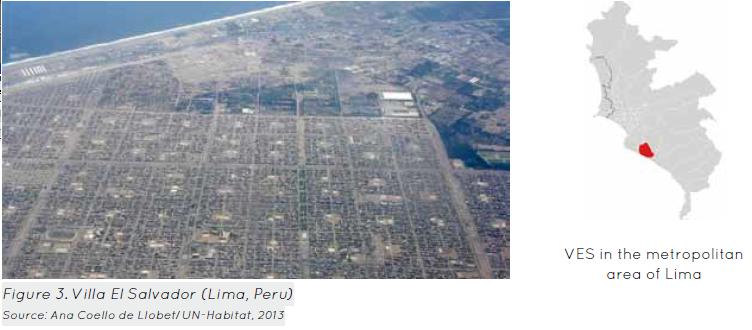

The example of Villa El Salvador, an urban district on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, that was developed from a shanty town into a formal district of Lima between 1971 and 1983, shows some interesting lessons. The original settlement design in 1971 only marked street and plot limits; the assignment of lots was largely self-organised through a communal organisation. Today, the district has over 380,000 inhabitants (see Figure 3), and 84 per cent of houses are owned by the inhabitants (INEI census, 2007 data). This planned city extension is generally deemed a success due to its simple master plan and mixed use design, which allowed for future growth, incremental improvement and strong ownership by the inhabitants.

The issues of sprawl, segregation and connectivity have been actively addressed in Villa El Salvador:

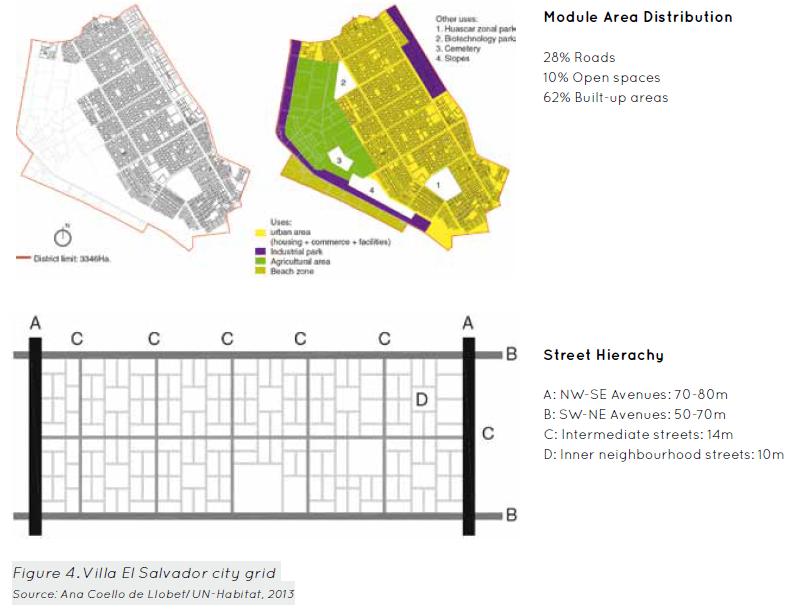

Compactness versus sprawl. The block module and plot structure of Villa El Salvador (see Figure 4) allow for different densities. This flexible urban pattern structure can be easily implemented, extended and densified, reducing the effects of uncontrolled sprawl. The neighbourhood can be easily extended by adding modules to existing ones, and existing plots can be densified according to the exigencies of urban development.

Integration versus segregation. One basic principle in the early stages of development was to avoid becoming a dormitory town, and hence the focus was on creating jobs in a mixed-use environment. Part of the area was designated for industrial and agricultural uses (“Before the houses, build factories!”). Likewise an inclusive public facilities policy, emphasising service to all households, was also adopted.

Connectivity versus congestion. The proposed, well-articulated road network (again see Figure 4) is well connected to the existing train and road network at the national (Pan Americana Sur), metropolitan and local level. The basic planning module of Villa El Salvador provides for 28 per cent street space, 10 per cent public space and 62 per cent built-up area – proportions that allow for sufficient provision of street and public space and adequate vehicular and pedestrian connections within the neighbourhood.

UN-Habitat and planned city extensions

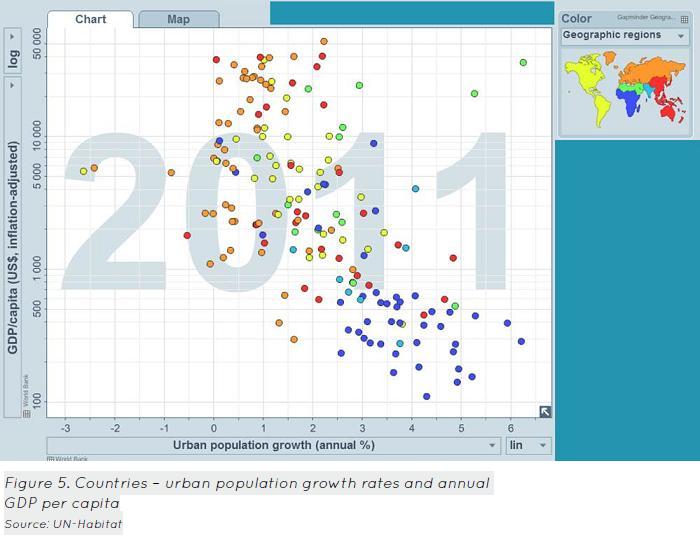

The majority of future urban population growth will take place in small‐ to medium‐sized urban areas in developing countries, most notably in Africa and Asia (Cities and Biodiversity Outlook, 2013). Most in need of planned city extensions are those rapidly growing cities in developing countries (i.e. with low GDP per capita; see Figure 5), where local authorities often lack the capacity needed to promote effectively sustainable urban development.

Drawing on lessons from Villa El Salvador and numerous other experiences, UN-Habitat is working with a wide range of partners from different levels of government and a variety of other sectors to help plan city extensions in a number of countries. In Rwanda, Kenya, Egypt, Philippines, Colombia, Haiti and elsewhere, we are supporting local authorities in rapidly urbanising agglomerations to provide the appropriate legal, institutional and financing frameworks for sustainable city extensions. Our work reflects the following five principles for planned city extensions, with corresponding guidelines:

Adequate space for streets and an efficient street network. The street network should be adequate not only for vehicles and public transport but also for pedestrians and cyclists. UN-Habitat’s research indicates that, in high density, mixed-use urban areas, at least 30 per cent of land should be allocated for roads and parking, and at least 15-20 per cent should be allocated for open public space. To develop sustainable mobility, the design of the street network should differ from the modernist practice in the following aspects:

- Public transport, walking and cycling should be encouraged.

- Road hierarchy should be highly interconnected.

- Sufficient parking space should be provided.

Relatively high density. As previously discussed, relatively high density development offers numerous socio-economic and environmental benefits. High density development:

- Slows down urban sprawl because high-density neighbourhoods can accommodate more people per area.

- Reduces transport needs, especially for motorised transport, reduces parking demand, and increases support for public transport.

- Increases energy efficiency and decreases pollution.

- Decreases the costs of public services such as police and emergency response, school transport, roads, water and sewage.

- Provides for better community service.

- Allows for an improved provision of public open space.

Mixed land use. Advocates of mixed land use development seek to develop a range of compatible activities and land uses close together in appropriate locations, in design modules that are flexible enough to adapt over time to the changing market. The purpose of mixed land use is to create local jobs, promote the local economy, reduce landscape fragmentation and support mixed communities. Mixed land use can be applied at different spatial levels: city, neighbourhoods, blocks and buildings. Mixed land use reduces urban sprawl, car dependence and traffic congestion, and increases vitality of urban centres.

Social mix. Encouraging the proximity of rich and poor within the urban fabric promotes the cohesion of and interaction between different social classes in the same community. It helps to ensure accessibility to equitable urban opportunities by providing different types of housing. Social mix provides the basis for healthy social networks, which in turn are the driving force of city life. Social mix is a socio-spatial concept, with the following objectives, all of which will increase social resilience within the city:

- Promoting more social interaction and social cohesion across groups

- Generating job opportunities

- Overcoming place-based stigma

- Attracting additional services to the neighbourhood

- Sustaining renewal/regeneration initiatives.

Social mix and mixed land use are interdependent and promote each other. Mixed land use and appropriate policy guidance lead to social mixing. In a mixed land use neighbourhood, job opportunities are generated for residents from different backgrounds and with different income levels. People live and work in the same neighbourhood and form a diverse social network.

Limited land use specialisation. Providing for flexibility in land use helps to ensure the implementation of mixed land use and increase economic diversity. Limiting overly rigid land use specialisation is important in creating mixed land use.

The five principles presented above for developing more sustainable planned city extensions are strongly interrelated and mutually supportive. Together they offer a basic recipe for urban development that provides for more compact, inclusive and connected cities. This approach can not only help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build resilience, but also confers important other co-benefits.

Habitat III: a New Urban Agenda

The third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in 2016 will offer an opportunity to reinvigorate the global commitment to sustainable urbanisation, and for member states to agree on a New Urban Agenda. Habitat III will be the first UN global summit after UNFCCC COP21 in Paris, and the adoption of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda; it thus will offer a chance to view the results of those efforts through an urban lens. The preparatory process and the Conference itself will afford a unique opportunity to discuss the important challenge of how cities, towns and villages are planned and managed, in order to fulfil their role as drivers of more sustainable development, and leading partners in the global effort to address climate change.

_(1)_400_250_s_c1.png)