Air quality and urbanisation – drivers of climate change

Dr Fatih Birol, Executive Director, International Energy Agency (IEA), makes an urgent case for stepping up energy efficiency and fuel pollution measures in emerging megacities.

Cities are at the heart of the energy landscape, currently accounting for two-thirds of primary energy demand and 70 per cent of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. By 2050, the urban population will grow from half to two-thirds of the global population. Under current trends this would result in urban energy demand rising by 70 per cent, with the vast majority of this growth coming from cities in emerging economies and developing countries.

In the megacities that are rapidly expanding across the developing world, decision-makers are struggling to reconcile the imperatives of urbanisation and energy access, economic growth and social development. Yet at the same time, there is an urgent need to improve urban air quality and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the twin challenges of urbanisation. With energy production and usage the most important sources of air pollutant emissions – contributing 85 per cent of particulate matter and almost all of the sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides – rising demand for energy services may seem at odds with these objectives.

This is not an abstract problem. In those smog-choked cities, close to 18,000 people die every day from the effects of air pollution – 6.5 million premature deaths per year, or more than one in nine deaths worldwide. While these devastating impacts of air pollution are felt in both the wealthiest and poorest nations on earth, it is in the world’s emerging economies, where the urbanisation process is still far from complete, that we find the greatest opportunities for finding a healthier path.

Policy-makers in these countries face a clear choice: they can lock in highly polluting infrastructure that damages the climate and human health, or chart a different course – one that delivers low-carbon growth, cleaner air and a sharp improvement in health, averting millions of preventable deaths each year while at the same time taking significant steps towards meeting targets under the Paris Agreement.

Practical steps forward

In recognition of the importance of the interlinked issues of urbanisation, air pollution and climate change, the IEA has dedicated two major research efforts to this area over the past year. Energy Technology Perspectives 2016 (ETP2016) focused on technology and policy opportunities to accelerate the transition to sustainable urban energy systems, while the World Energy Outlook Special Report: Energy and Air Pollution analysed the global outlook for energy and air pollution and proposed a pragmatic scenario to deliver both climate and air pollution improvements.

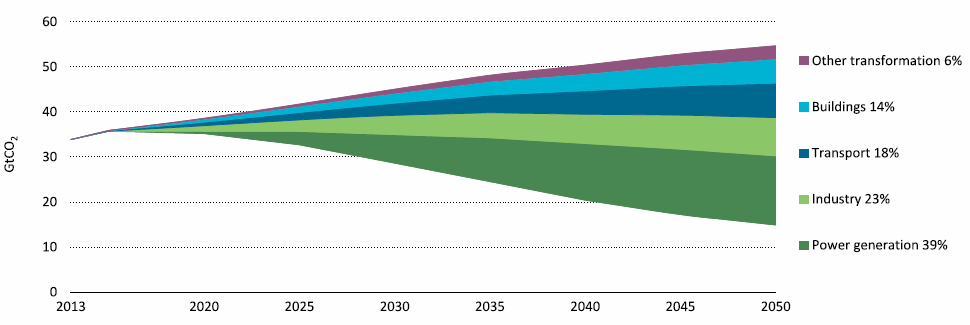

The analysis in ETP2016 lays out an ideal potential future in its 2°C Scenario (2DS). In this scenario, the rising demand for energy driven by urbanisation is still met, but smart and sustainable policy and technology choices mean that economic growth and booming populations do not lead to skyrocketing energy demand and emissions growth (Figure 1).

This outcome can only come about through a set of actions that collectively avoid the lock-in of high-emissions urbanisation. Policy at the national level must encourage the deployment of clean energy technologies, and include greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, carbon pricing mechanisms, and investment in energy research, development and demonstration.

But these targets must then be complemented by action at the local level. To meet their renewable energy targets, cities can provide detailed solar maps giving valuable information on expected energy yields and installation costs for buildings and houses in various neighbourhoods, for example. On transport and fossil fuel emissions, cities can also invest in the long-term development of walking and cycling infrastructure. For energy efficiency, cities can take a leading role in adopting, monitoring and enforcing building energy codes for new construction.

Urban density offers a significant opportunity for emissions reductions as less energy is needed to fulfil the same needs for things like heating and cooling. Equally, urban infrastructure design can curb transport-related carbon emissions by reducing trips and trip distances, shifting activity to public transport, and promoting adoption of more efficient, low-carbon vehicles. Local and national policy decisions are key to shaping this future, through regulations on land-use planning, building codes and vehicle standards, pricing policies, and support for uptake of non-motorised and electric mobility. If this full transformation of urban energy systems could be realised, it would mean that CO2 emissions from urban energy use could be reduced by 75 per cent in 2050 compared with the track we are on today.

This long-term shift ultimately moves the energy system away from fossil fuel combustion, while also making significant progress on combating air pollution. This is because the root causes of air pollution can be found in the energy sector. Coal is responsible for sulphur dioxide emissions – a cause of respiratory illnesses and a precursor of acid rain – while transport fuels, such as diesel, generate nitrogen oxides and particulate matter that can contribute to serious health issues such as asthma, lung cancer and heart disease. Cities can easily become pollution hotspots. The impact of vehicle emissions is heightened by the fact that they are discharged at street level, where pedestrians walk and breathe. This is a problem that will not go away tomorrow, despite strong efforts.

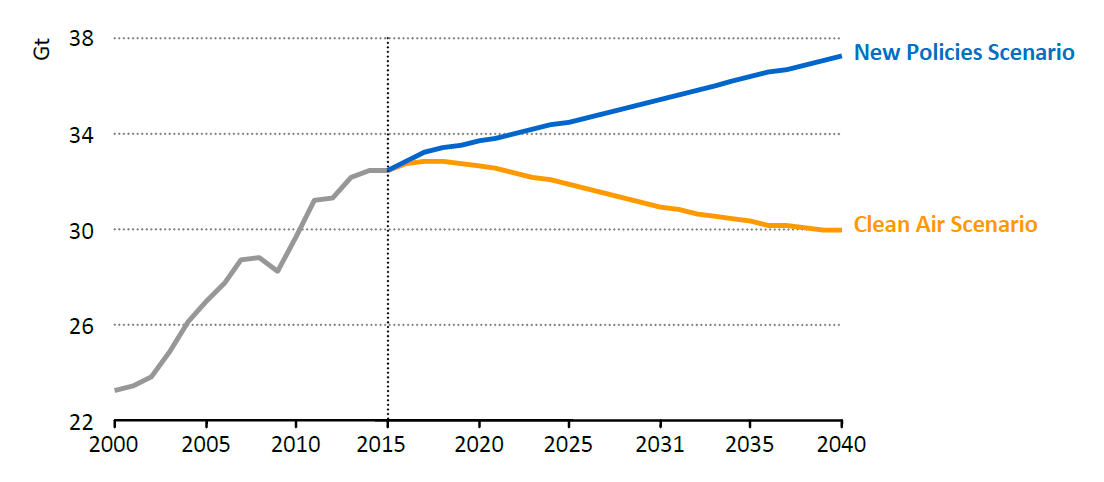

This makes the urgent case for taking action today. In the near term, the World Energy Outlook Special Report: Energy and Air Pollution proposes a set of policies to avoid pollutant emissions while at the same time taking steps towards fulfilling Paris Agreement obligations. These policies include, among others, stronger efficiency policies for appliances and buildings, higher vehicle emission standards, reduced sulphur content in fuels, and a phase-out of fossil fuel consumption subsidies. This ‘Clean Air Scenario’ requires a small increase of 7 per cent in investment. But the benefits are massive: saving over 3 million lives in 2040 while providing energy access for all and contributing to a peak in global CO2 emissions by 2020 (Figure 2).

Energy access

In 2013, an estimated 1.2 billion people – 17 per cent of the global population – lacked any access to electricity, and an estimated 2.7 billion relied on burning wood, charcoal, and agricultural waste to meet their cooking and heating needs, typically using inefficient stoves in poorly ventilated spaces. Solving both these problems together, expanding energy access and improving air quality can be mutually supportive. Overall, the extra impetus to the energy transition from the Clean Air Scenario means that global energy demand would be 13 per cent lower in 2040 than otherwise expected and, of the energy that is combusted, three-quarters would be subject to advanced pollution controls. These measures would have a dramatic impact on key pollutants, reversing the current trend towards worsening air pollution in many countries, particularly fast-growing Asia and Africa.

On top of these benefits, the Clean Air Scenario provides a pragmatic first step toward achieving the climate goal agreed in the Paris Agreement. For developing countries embarking for the first time on CO2 emission reduction goals, the associated benefits for air quality could be a powerful driver of action.

Confronting the twin challenge of CO2 emissions and air pollution means dispensing with short-term thinking and stop-gap solutions. IEA analysis shows that proven energy policies and technologies can chart a new sustainable path for urbanisation that delivers major cuts in air pollution around the world and bring health benefits, broader access to energy and improve sustainability. In the spirit of the Paris Agreement, this is a time for bold, ambitious and strategic decision-making.

It is no exaggeration to say that the global fight against climate change and air pollution will be won or lost in the megacities of the world’s emerging economies. Cities are naturally positioned to make these kinds of changes. In my role as Executive Director of the IEA I have been fortunate to travel to many of the world’s great cities, and I have seen first-hand their great potential. The density of human, economic and intellectual capital in these cities can and should be a driving force for the acceleration of clean energy development and deployment for the decades to come.

Read the full Climate Action 2016/17 Publication here