Compact cities to address climate change

Compactness is an important attribute of the most efficient and sustainable cities. Not only can there be environmental advantages such as cutting transport distances and encouraging citizens away from motorised transport, but social and economic benefits are also available if careful planning is undertaken to manage expansion.

In ‘A New Paradigm for Urban Planning’, UN-Habitat’s contribution to Climate Action 2012, we took the opportunity to sketch out in broad terms a ‘new urban agenda’. This article concentrates on one important element of that agenda: the compact city.

The current global trend of urbanisation is well established. The urban population has increased nearly fivefold between 1950 and 2011 (United Nations, World Urbanization Prospects), and by 2030 demographers project that over 60 per cent of the global population will reside in cities. However, inevitable though the general trend appears to be, the form that urbanisation will take can be guided by effective planning. Cities are human constructs and we possess, now more than ever, the knowledge and technology required to shape urban life to better support human development.

This period of rapid urbanisation, particularly in developing countries, provides a unique opportunity to control the urban structures that will be with us for many generations. And all signs point to one broad type of urban form that we should promote: the compact city.

Why compact?

We should embrace policies that promote the compact city for various reasons, including to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. Cities emit a substantial proportion of the world’s greenhouse gases (GHGs) that come about through anthropogenic causes. Depending on definitions as to what size of human settlement constitutes a city and whether one uses figures based on consumption or production, estimates of this proportion can vary from 30 to 70 per cent (UN-Habitat, Global Report on Human Settlements 2011 – Cities and Climate Change). While there are a range of policies available to reduce cities’ emissions, one fundamental approach involves promoting compact urban development. There is a general correlation between higher urban density and lower emission levels (see Figure 1 below).

.jpg)

Figure 1. City density versus GHG emissions per capita

A number of reasons can be given for this. Firstly, dense urban settlements usually provide opportunities for lower emission forms of transport. Urban density is one of the most important factors influencing the amount of energy used in private passenger transport, and therefore has a significant effect on GHG emissions. If all other variables are controlled, one study found that an increase in density of 1,000 housing units per square mile leads to a 1,200-mile reduction in vehicle miles per household per year (Brown et al, cited in UN-Habitat, Global Report on Human Settlements 2011). A similar study found that a doubling of the average neighbourhood density was associated with a 20-40 per cent decrease in vehicle use per household, leading to a corresponding decline in GHG emissions (Gottdiener and Budd 2005, cited in Global Report on Human Settlements 2011).

_06v2.JPG)

Another reason why compact development reduces emissions relates to land use change. As cities grow horizontally they consume surrounding green fields; previously vegetated areas (one form of ‘carbon sink’) are cleared for built environments. Compact development, therefore, may reduce the GHG emissions associated with land-use change as compared with urban sprawl.

The compact city also yields other environmental benefits. Preparation of land for buildings may reduce permeable surfaces, fragment ecosystems and alter micro-climates. Again, if done carefully (for instance with attention to geographical and environmental features such as fragile ecosystems), compact development may reduce those negative impacts.

Social and economic dimensions

Compact urban form not only has positive environmental implications but also may yield social and economic benefits. Much of the growth in cities in developing countries is occurring as peri-urban informal settlements. UN-Habitat’s State of the World’s Cities Report 2012/13: The Prosperity of Cities suggests two benefits for the urban poor from compact development. Firstly, the compact city may enhance livelihoods for the urban poor through better access to economic opportunities and affordable mobility within the urban environment. Secondly, a compact development pattern may lower degrees of social segregation through closer proximity of affordable housing options to places of work. Ensuring that a variety of housing types are within the reach of basic services and infrastructure further helps to ensure the urban poor are not marginalised.

More generally, urbanisation has shown a powerful and positive correlation with economic development. This is due to the agglomeration and proximity advantages of economic activities which are the products of a compact and connected city. The State of the World’s Cities Report 2012-13 notes that these intrinsic city-level factors benefit firms by allowing them to locate near customers and suppliers (reducing transport and communication costs), take advantage of increased flexibility between labour supply and demand, access a wider range of shared services and infrastructure, and benefit from concentrations of specialist industries.

Trend away from compactness

Despite the considerable benefits that thus can be derived from the compact city, the general trend in urban development over the past century has been away from density towards urban sprawl. The average density of built-up areas in both developed and developing country cities is declining, and some of the largest decreases can be seen in developing countries (Figure 2). It is estimated that the total population of cities in developing countries will double between 2000 and 2030, but their built-up areas will increase threefold over the same period, from about 200,000 to 600,000 sq km (World Bank, cited in UN-Habitat’s Global Report on Human Settlements 2011). The post-World War II era of cheaper fossil fuels, and growing automobile ownership in developed countries, encouraged less dense patterns of urbanisation. Now with the urgency of climate change and higher fuel prices, a compact urban form is critical to bring together employment and housing opportunities and to reduce commuting distances and associated GHG emissions.

Complementary policies for compact cities

A compact urban form must be balanced with appropriate provisions of public space, particularly an efficient street network and public green areas. Streets facilitate the exchange of goods and the movement of people. They serve as the backbone of infrastructure networks including transport, drainage and electricity. Carefully planned street networks can facilitate efficiencies in these aligned critical infrastructure systems.

Public green space is a way to maintain the liveability of a compact city, providing respite within a dense urban environment. Well-chosen green areas, carefully developed and maintained, are also essential for supporting the ecological systems of the city. Cities can be greened while remaining compact. An example of effective greening comes from Chicago, where the city adopted a comprehensive plan titled ‘Adding Green to Urban Design’ in 2008; and in 2009 launched an ‘Urban Forest Agenda’. The Plan and Agenda include actions to improve the design of important green infrastructure areas in the city such as rooftops, building facades, landscaping around buildings and in parking lots, sidewalks, parkways and streets. Chicago recently reported 7 million sq ft (650,000 sq metres) of green roofs finished or under construction, 120 green alleys installed, and 6,000 trees planted in urban heat island communities.

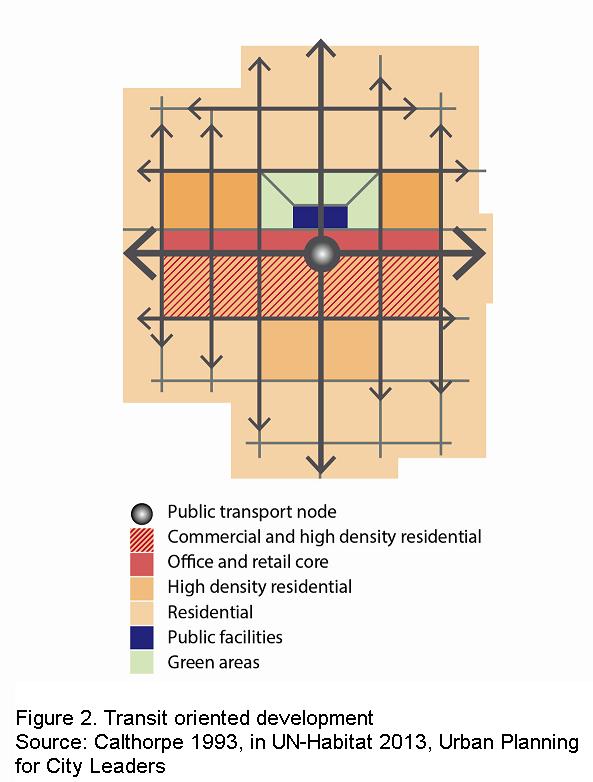

‘Transit oriented development’ is one way to achieve high density along with other positive outcomes. Under this approach, planners may concentrate dense development at certain points (Figure 3): along public transport trunk routes, areas in or around urban nodes (such as interchanges, public transit stops, economic centres), and on the periphery of open spaces to increase passive surveillance and safety.

The scale of densification should be context-specific and take into account such issues as cultural perceptions, building standards, housing demand, land and building costs and the supporting infrastructure systems. While the exact policies thus may vary according to context, the focus – particularly in the global South – should be on basic urban planning. Delineation of public versus private lands, and setting aside areas of green space, should be prioritised. These plans can be developed without detailed and expensive urban planning processes. This focused approach is particularly appropriate for developing countries that may have fewer resources to draw upon in urban planning processes.

Densification a priority

Encouraging compact development is just one strategy for creating more sustainable, liveable cities, but the current trend towards lower densities, combined with urbanisation and climate change, highlights the importance of this approach. To provide for expanding city populations and avoid uncontrolled urban expansion and its environmental impacts, urban planners should prioritise densification.

In 2015, UN-Habitat will host the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III). The conference will provide the opportunity for world leaders and stakeholders to outline and address the challenges of the present and future, including urban planning for a compact city. Habitat III will offer a platform to discuss the role that cities must play in climate change mitigation and sustainable human development in a world where the majority of people reside in urban areas. To avoid tackling the challenge of urbanisation and climate change as interconnected issues is to miss a significant opportunity for a better global future.

_400_250_s_c1.png)