Insights from Britain’s New Compliance Nature Market: Biodiversity Net Gain

The launch of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) was the biggest shake-up to the British planning system in decades. This new legal requirement, which aims to leave nature in a measurably better state than it was before development, is already yielding positive results. With even greater ambition, it could be transformational for nature. In this blog, I introduce how the world’s largest biodiversity compliance market is working on the ground, and how The Wildlife Trusts in England are engaging with it.

About The Wildlife Trusts

Since our foundation in 1912 as The Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves, The Wildlife Trusts have recognised nature’s remarkable ability to address both societal and environmental challenges—what is now commonly referred to as nature-based solutions. Today, The Wildlife Trusts are a grassroots movement of independent charities, comprising 46 Wildlife Trusts and 24 consultancies covering the whole of the UK, Alderney, and the Isle of Man, alongside a central charity, the Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts (RSWT). Backed by almost one million members, we are Britain’s sixth-largest landowner, managing over 2,600 nature reserves and overseeing more than 100,000 hectares of land across all types of British habitat.

The Wildlife Trusts in England have been influencing the evolution of BNG for over a decade. This has taken many forms—from early thinking and piloting in 2012, to testing and contributing to multiple iterations of the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) biodiversity metric and advocating for clear commitments on BNG in the UK Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan and other key legislation and policy.

At the local level, Wildlife Trusts have also long advocated for the inclusion of BNG policies in local plans and promoted voluntary BNG. More recently, many Trusts have been preparing to become high-quality providers of off-site BNG units, while also establishing advisory services for both developers and landowners.

Lady orchids (Orchis purpurea) in protected area of brownfield development site. Credit: Terry Whittaker/2020VISION

How Does BNG Work?

BNG requires developers to achieve at least a 10% net increase in biodiversity compared to pre-development conditions. This represents a significant step forward in ensuring measurable, positive outcomes for nature.

The requirement can be met by restoring or creating habitats on the development site. Where this is not possible, developers may deliver the units off-site—either by creating them directly or purchasing them from a local delivery partner or ‘habitat bank.’

As a last resort, statutory BNG credits can be purchased from the government.

Initially, BNG applied only to ‘major’ new developments—those with 10 or more dwellings or covering over 0.5 hectares. In April 2024, the requirement was extended to include ‘small’ sites (fewer than 10 dwellings or under 1,000 square metres of commercial space), and later this year, it will be extended again to include Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects, such as major road or rail works.

A key principle in delivering effective BNG is the mitigation hierarchy. This framework requires developers to prioritise avoiding, reducing, and mitigating nature loss on-site before considering off-site compensation through BNG units. All habitats created for BNG must be managed and monitored for at least 30 years to demonstrate the planned ecological uplift. When implemented well, BNG can both protect vital nature sites (by incentivising avoidance) and generate new funding to support nature’s recovery.

Early Insights: How Is BNG Working in Practice?

There was initial scepticism about how the new compliance market would develop. Soon after its launch, the National Audit Office observed: “The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) launched a novel and complex biodiversity scheme without having all elements in place to ensure its long-term success.”

Concerns about the viability of the emerging market were further heightened by the election of a Labour government last July, with its commitment to building 1.5 million homes.

At first, very few sites were listed on the BNG register with off-site habitat units available for sale—likely due to the new and initially lengthy process of legally securing these sites—making it difficult for developers to source local, off-site solutions.

However, after a slow start, the number of habitat banks is now rising rapidly as players (including Wildlife Trusts) enter the market. A growing pipeline of off-site BNG units is becoming available to developers. This increase has been supported, in part, by the introduction of ‘Responsible Bodies’. These organisations—such as charities or businesses with a conservation focus—can now enter into legally binding ‘Conservation Covenants’ with landowners to secure the long-term protection of natural or heritage features (such as BNG units). Many are finding Conservation Covenants to be a simpler and quicker alternative to traditional planning agreements.

Despite this progress, demand for off-site BNG units is currently lower than Defra originally anticipated.

A University of Oxford study of pre-mandatory BNG delivery found that off-site provision accounted for just 7.4% of sampled developments. This was echoed in research by The Environmental Partnership, which reviewed 503 BNG-compliant planning applications (April–Oct 2024) from 120 English local authorities. It found that 67% of applications sought to deliver BNG entirely on-site, with off-site units accounting for less than 10% of those delivered.

The Wildlife Trusts’ Service Offering

To date, five Wildlife Trust sites offering BNG units are registered, with a further pipeline of over 70 sites in development across England—many of which have already made pre-mandatory sales to developers.

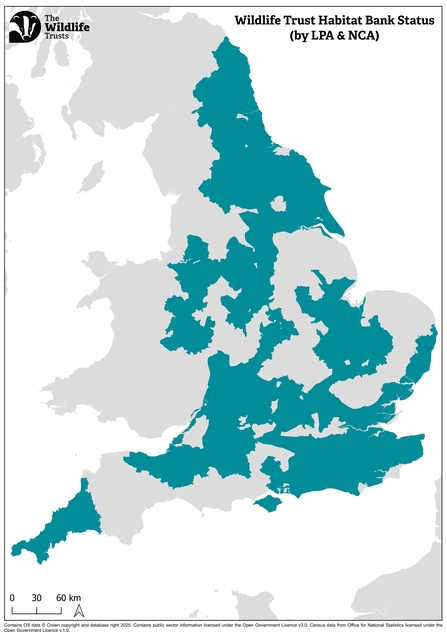

Local Planning Authorities and National Character Areas where The Wildlife Trusts have habitat banks live or in development.

Collectively, these sites will provide over 6,000 BNG units across 46 Local Planning Authority (LPA) areas. Highlights include:

- Ludgershall Meadows, Buckinghamshire: A patchwork of meadows on the Upper River Ray floodplains, home to scarce wading birds such as lapwing and curlew.

-

Duxford Habitat Bank, Oxfordshire: Situated in the Upper Thames conservation area, with plans to restore river, floodplain, and wetland habitats.

-

Wild Whittington, Derbyshire: A rewilding site featuring woodland, scrub, wetland, and grassland to form a vital green corridor in the Chesterfield area.

-

Flack Field, Cambridgeshire: Strategically located beside Fulbourn Fen SSSI and within the emerging Local Nature Recovery Strategy.

-

Fleam Dyke, Cambridgeshire: Also within the Local Nature Recovery Strategy, supporting adjacent SSSI sites and contributing to climate resilience.

Duxford Old River habitat bank, in Oxfordshire, England.

The Wildlife Trusts and their consultancies are also providing local, expert advice throughout the development process—from planning to post-construction. Two local Wildlife Trusts have been registered as Responsible Bodies, enabling them to secure long-term protection for biodiversity through Conservation Covenants.

Room for Improvement: Aim High for Real Net Gain

Concerns remain that the current BNG regulations—requiring only a 10% gain—may not be sufficient to contribute meaningfully to the UK government’s ‘30 by 30’ objective (protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030).

For example, a study of pre-mandatory BNG found that despite an average 20.5% increase in BNG units across developments, there was still a net loss of greenspace of over 30%.

At The Wildlife Trusts, we have consistently advocated for a more ambitious threshold. A 10% gain is low enough to fall within the margin of error for habitat creation, which means it may not deliver genuine, additional biodiversity benefits. Furthermore, this low target is suppressing demand for off-site habitat compensation—undermining BNG’s potential to deliver nature recovery at scale.

To ensure BNG delivers meaningful, lasting benefits for nature, we strongly encourage developers to aim for at least a 20% gain. This higher ambition would ensure their developments leave a truly positive legacy for wildlife.

What’s Next for BNG in the UK?

BNG continues to evolve, and its long-term impact remains to be seen. Importantly, data from the past year may not provide a fully representative baseline, due to a surge of applications submitted just before BNG requirements came into force, and the exploitation of various regulatory loopholes. It will be critical to monitor how these early distortions play out over time and whether further policy refinements are required.

That said, the scale of BNG is expected to increase significantly when it is extended to Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) in late 2025. These include major developments across energy, transport, water, and waste sectors—such as power stations, transmission lines, wind farms, and large-scale road and rail projects. This is likely to trigger a sharp increase in demand for off-site BNG.

Internationally, interest in the BNG model is growing. Policymakers, conservationists, and corporate leaders in other countries are now exploring how similar frameworks might be adapted to different legal and ecological contexts. We welcome opportunities to share insights and support the global advancement of nature-positive economic models.