Sustainable investment fund labeling framework: An apples-to-apples comparison

The list of sustainable investment (SI) frameworks guiding portfolio design is long and continues to proliferate. But with each one having different stated aims, scope and criteria, how should fund issuers navigate this complex landscape?

The list of sustainable investment (SI) frameworks guiding portfolio design is long and continues to proliferate. Many countries now have their own ESG labels to ensure a certain quality of SI for the growing pool of funds targeting sustainability goals. But with each one having different stated aims, scope and criteria, how should fund issuers navigate this complex landscape?

A white paper by Anna Georgieva and Saumya Mehrotra of Qontigo’s Sustainable Investment team examines the criteria used in the 12 most important European frameworks setting standards for SI products, including Belgium’s Towards Sustainability label, the German-speaking countries’ FNG Label, and France’s SRI and Greenfin labels. They provide a like-for-like comparison of exclusionary criteria and portfolio-construction techniques as applied in each individual label. The authors’ motivation is to highlight the discrepancies among the various labels and inform interested stakeholders about the intricacies of the current situation.

The authors present a detailed analysis of the various frameworks, after narrowing down the common set of criteria under the labels as they relate to:

- which companies are excluded from portfolios (negative screening), and

- how portfolios are constructed above and beyond these exclusions.

The analysis seeks to answer some key questions for the asset-management industry, including:

What are the existing labels’ aims? Which criteria are aligned with each other and where do they diverge?

Is it actually feasible to design a financial product that aligns with all labels? What are the implications for the scalability of SI products?

What are the effects of attempting to limit the number of labels to the bare minimum through standardization, as opposed to encouraging divergence on the grounds that there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to SI?

What does this all mean for the ultimate goal of transitioning to a more sustainable economy?

Trends in ESG labels

ESG labels have gained significant preeminence in recent years as tools to provide transparency and drive capital towards sustainability goals. The entry into force of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) in 2021 — a much-followed, de-facto label — is already prompting many fund companies to adjust their offerings. Labels have the potential to influence the success of the sustainability transition, the whitepaper’s authors note, helping avoid misallocation of funds and greenwashing, and guaranteeing a certain normative quality for end investors.

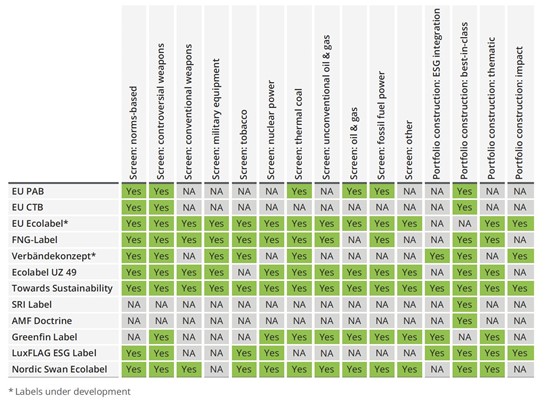

However, as they also make clear, the labels currently form a highly divergent and fragmented landscape (Figure 1). Ironically, alignment with European Union rules is often in itself a source of divergence since SI is not interpreted uniformly in the different pieces of EU legislation. The EU Taxonomy, when finalized, could change this.

Figure 1 – Overview of the analysis

Source: Qontigo, ‘Sustainable investment fund labeling frameworks: An apples-to-apples comparison.’

The study first identified three major categories in terms of the labels’ key focus:

- broad sustainability

- broad environmental

- specific environmental focus on climate.

Second, the authors manually interpreted and classified the labels into three product design buckets:

- exclusions only

- minimum performance only

- a combination of both.

Analyzing each label’s criteria is key to recognize trends and help guide investors in the path forward in portfolio design. Some take-aways from the analysis show that norms-based exclusions are now a must, and weapons and energy dominate product-involvement screens. However, the thresholds applied differ vastly. Interestingly, the authors note that while exclusions based on environmental criteria are common, social and governance criteria are less so but growing in importance. Another emerging trend, they write, will be the use of exclusion indicators that progress and become more stringent through time, to incentivize companies to transition.

With respect to portfolio construction, the authors observe that ESG integration is necessary but not always seen as sufficient to classify as an SI strategy anymore, not least because it is now a regulatory baseline for all funds under the SFDR. Best-in-class is currently the most common strategy, with thematic and impact gaining more relevance. Engagement approaches are increasingly recognized as a powerful lever to drive real-world impact.

The ‘impossible’ pan-European ESG-labelled fund

In an illustration of the challenges faced by fund issuers, the authors analyze what thresholds a product would need to meet if it was designed to be widely distributed across European markets.

What would such a product based purely on common exclusions look like? Would it even be feasible from a portfolio construction and sales perspectives? Readers can find the answer in the study, but two warnings emerge from this exercise. Firstly, given the lack of harmonization, fund issuers may fail to achieve scalability, slowing down the mainstreaming of sustainable investing. Secondly, the application of the highest common denominator for each criterion among the various labels can lead to highly restrictive criteria that could exclude systemically important companies in the sustainable transition.

“There is very little common ground between labels as to what constitutes a sustainable investment product,” the authors write. “Consequently, it can be argued that failure to establish basic common ground would result in major drawbacks for both investors and the SI agenda at large.”

Recommendations for fund issuers

In the face of these challenges, there are key takeaways for fund issuers, the authors write. In particular, they recommend staying abreast of relevant developments in order to play an informed and active role in policy engagement and regulatory consultations. To future-proof products, it is also important to adhere to standards that are both science-based and that incorporate elements incentivizing the real economy towards the sustainable transition, they add.

“Labeling, to the extent it is deployed as a tick-box exercise, is frequently less impactful for achieving this goal than a spectrum of other actions such as supporting sustainability R&D and participating in collaborative engagement investor initiatives,” they write. “Such actions could have a more positive impact on differentiation and serve the overall industry.”

The whitepaper will prove to be a useful source for fund issuers, investors and intermediaries to understand a topic that will only grow in importance day after day.

About Qontigo

Qontigo is a leading global provider of innovative index, analytics and risk solutions that optimize investment impact. As the shift toward sustainable investing accelerates, Qontigo enables its clients—financial-products issuers, asset owners and asset managers—to deliver sophisticated and targeted solutions at scale to meet the increasingly demanding and unique sustainability goals of investors worldwide.

Part of the Deutsche Börse Group, Qontigo was created in 2019 through the combination of Axioma, DAX and STOXX. Headquartered in Eschborn, Germany, Qontigo’s global presence includes offices in New York, London, Zug and Hong Kong.